Sign-up to our mailing list

Kits and Pieces: why STEM kits for kids are about play rather than just education

This piece was originally written and published by Stuart Dredge, and is republished here with his permission – because we think it’s spot-on!

Stuart is a UK-based journalist who writes mainly about the music industry, digital media and children’s technology. He co-founded the website ContempoPlay, is editor-in-chief for Music Ally, and writes the apps, games and tech pages for The Week Junior.

Harry Potter and Marvel’s Avengers are among the famous characters taking on a new adventure: helping children learn computer-programming skills.

British company Kano is launching its £100 Harry Potter Kano Coding Kit in October, which will get children to build a magic wand then use it to complete coding challenges in a companion app.

American firm LittleBits is already selling its £150 Avengers Hero Inventor Kit, based on Marvel’s superheroes. The kit involves building arm-worn armour, then customising its look and sound with an app. It follows a previous kit based on Star Wars.

These products are part of a boom in gadgets and toys for children based on STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) topics. Research firm Juniper Research predicts that so-called ‘smart toys’ will grow from a £4.6bn market in 2018 to £13.9bn by 2023.

The Kano and LittleBits products reflect a trend for ‘kits’ that combine building physical objects with programming on a tablet, computer or smartphone.

“Tech-curious kids and their parents are just as interested in tinkering with hardware and messing about with that as they are with software,” says Alex Fleetwood of Sensible Object, the startup behind tech-infused board games Beasts of Balance and When In Rome.

“It’s about kids learning through play, and through exploring and inventing,” says LittleBits’ senior product designer Elaine Khuu, who thinks that debates about children’s digital habits are steering parents towards these products.

“There is an issue of screen time. More and more kids are spending time on screens, for example passively watching YouTube videos. We’re using the screen, but we’re using it to teach them how to invent and how to make… We believe we can make screen time something that’s super-positive and powerful in a kid’s life.”

LittleBits is one of the veterans in this world of STEM toys, with products that it aims at “kids aged eight to infinity” — with Khuu adding that children as young as four years old have been enjoying them.

The UK has a cluster of startups creating these products. Gloucester-based OhBot makes a kit for children to build a robotic head, then control it by connecting it to a computer and programming instructions, for example.

London-based Tech Will Save Us has sold hundreds of thousands of STEM kits since it was founded in 2012, from conductive-dough kits that teach children about electricity to another Avengers-branded product: the Electro Hero Kit. Its latest two kits focus on creativity: sewing and bicycle lights.

“Even the most technical of individuals have a fear of kids spending too much time on technology, and absorbed in screens. They want their kids to be social, to be moving, to be outside. It feels right to have a mix of things,” says CEO Bethany Koby.

“We see products that are encouraging kids to use technology as a creative medium, rather than as an end in itself, is what really gives parents a feeling that something good is happening. And remember: kids aren’t afraid of technology at all: it’s the parents who are scared of it!”

She adds that this is also true of politicians and education bosses, who are well aware that there’s a big demand and not enough supply for skilled people in the technology industry — the so-called ‘skills gap’ that is driving many of the efforts to get children interested in STEM subjects.

“There isn’t a government in the world that isn’t talking about the skills gap, and the necessity of kids interacting and being competent not just in technology, but in using it as part of problem-solving,” says Koby.

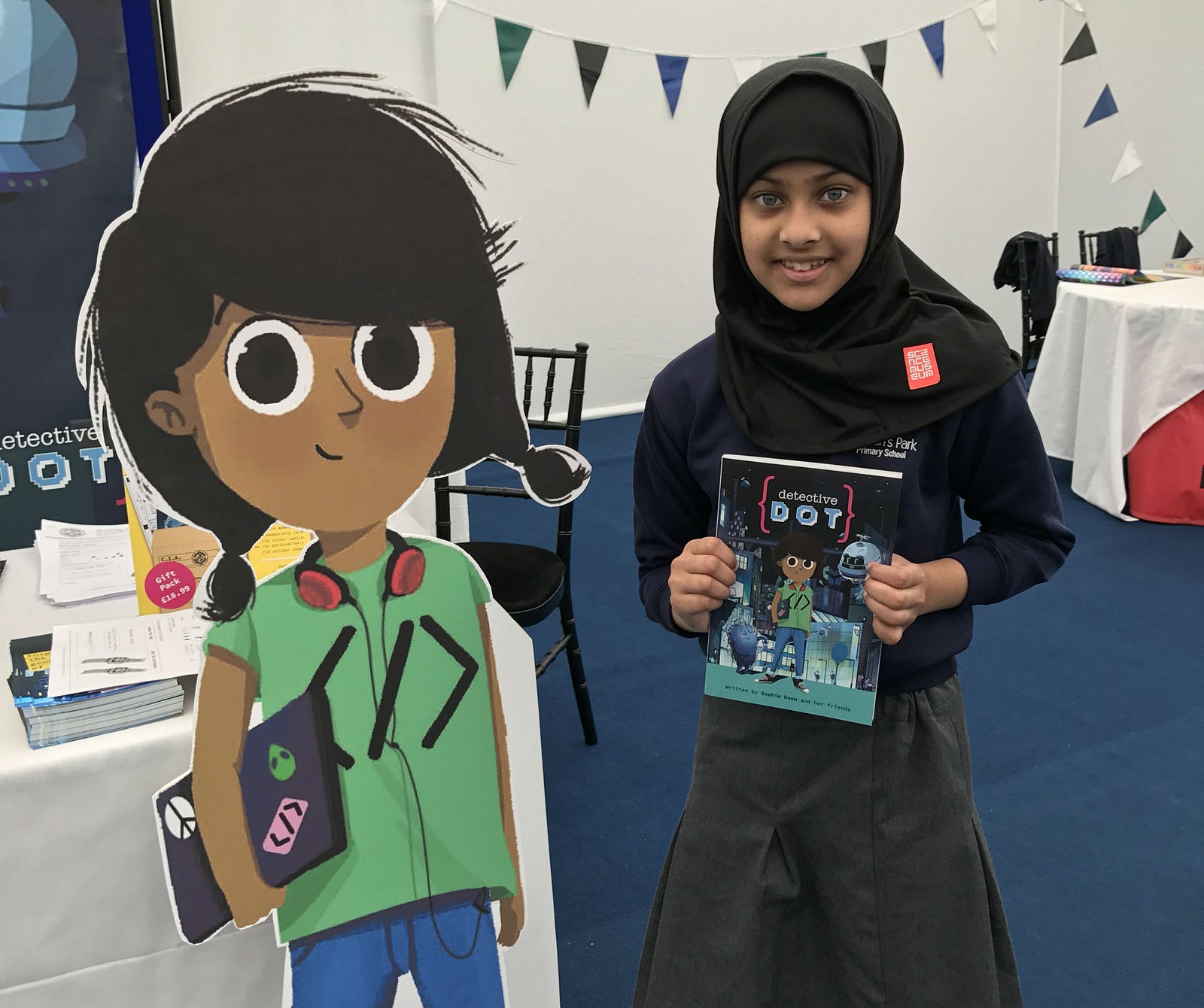

Another British startup, Bright Little Labs, focuses on books rather than gadgets as its physical STEM element. Its Detective Dot character’s stories are sold in a £19 ‘megapack’ that inducts children into a secret spying society.

“The whole premise is that I’ve never heard a kid say ‘I want to be a coder’ but every child I’ve ever met wants to be a spy!” says CEO Sophie Deen. “We’re using the engagement with characters and stories for an educational outcome.”

The physical element, even though it’s a book rather than hardware, is important here too.

“It was always going to be important for us to have a book or physical component. It’s so accessible. Computer science isn’t necessarily about sitting in front of a screen and writing a program. It’s about thinking about things, and the world around you,” says Deen.

“And for parents who are worried about screen time, it appeals having a book that they know is educating their kids about a world they’re growing up into, that the parents themselves might feel alienated by.”

Detective Dot has a girl as its hero, but Deen stresses that it’s not “for girls” — it’s a gender-neutral product, as are all the products released by the companies in this article.

“People see a girl lead and think ‘okay, we need more girl coders’. No, we need better role models for all our kids! Our space is quite good at that: with toys made specifically to engage kids with coding, people are passionate about making them gender-neutral,” says Deen.

“My problem is in more generalised approaches to STEM, when you see how STEM is portrayed in general cartoons and toys for kids. You really notice then that gender stereotypes aren’t going anywhere. But our challenge is to be a product for boys and girls.”

Elaine Khuu says that up to 40% of the children using LittleBits’ products are girls, and that the company takes a great deal of care with the images (and, indeed, with the children) used in its marketing to make it clear that its kits are gender-neutral.

From secret spy societies to robots and buildable kits, parents have a wide choice of STEM products. Choosing the ones that will encourage truly creative thinking can be a challenge, however.

“It’s like the difference between buying a Lego kit where you make something by following instructions, and using Lego to create your own ideas,” says Niel McLean, senior manager at BCS, the Chartered Institute for IT.

“With these products, it’s always worthwhile for parents to ask to what extent are the kids just filling in the blanks in coding, in a very mechanistic way? My number one question as a parent would be to what extent do they support open-ended problem-solving and kids pursuing their own ideas? And to what extent does the design itself constrain? ‘You’ve got to do it like this to make it work…’”

He stresses that many STEM kits answer these questions well, with their physical aspects lending themselves well to learning. “There is evidence that physical computing is motivating: making a real thing move or do something, rather than just moving stuff around on screens,” he says.

(This is also a point made by Lego Education’s senior marketing manager Joslyn Adcock, when she tells me about how the company’s WeDo 2.0 and Lego Mindstorms Education EV3 products are being used in schools with children: “Setting them tasks like creating a solution for a prosthetic hand that can move small objects around or designing an automatic floodgate to control water according to various precipitation patterns, gives them an understanding of how coding works in real-life and how it can be applied in practice.”)

LittleBits’ Khuu accepts the challenge laid down by McLean. “When we give kids instructions, it’s really just to give the foundation to understand how to use our tools,” she says.

“It’s a creative toolbox: we want them to take it on their own and then make whatever they can think of with it. We want kids to be creative with technology, not just be consumers of it. And our hope is that they can use what they’ve learned, then take it even farther than we’ve imagined.”

These companies are also balancing entertainment with education, although the demands of their young audience mean the former is the priority.

“This is play, ultimately. This is toys, this is games, and these are kids between the ages of four and 12. We’re not teaching them advanced calculus!” says Koby. “We lead with fun, and learning is a stealth part of the experience. It’s not the reason the kid is doing it.”

Deen agrees. “With everything we make, we want it to be educational and fun. If it’s fun and educational, it can pass. If it’s educational but not fun, we won’t do it,” she says.

“Entertainment is so important: if kids are engaged with the characters and the story, and they find what they’re doing exciting, they’re going to learn… a lot of the stuff we saw around coding in the past was ‘learn how to code in 10 chapters’.”

“That appeals to some kids, but not everyone, and it puts learning to code as the primary reason for doing something. But the primary reason for doing something, if you’re a kid, should be having fun! But if they’re having fun, they’ll be learning too.”

Fleetwood suggests that there is “quite a lot of chocolate-coated broccoli out there — stuff that is ‘good for you’ but they’re trying to make it palatable” while wondering how much long-term depth there really is in some STEM toys.

“Often with these products, you’re asking people to lay down quite a bit of money, and so that’s something you’re going to want your kids to play with a lot. But sometimes there are STEM products that don’t consider the long-term value very deeply,” he says.

“Kids are the ultimate arbiters. They have a phenomenal amount of choice, and without fail they’ll choose the most fun experience. They’re very rational consumers. You have to front up to that battle. If a STEM toy thinks it can compensate for lack of fun with educational value, it’s not going to last very long.”

That’s a common theme. “At the end of the day, we’re working with kids,” says Khuu. “If the kit is not fun, they’re not going to play with it, and they’re not going to be inspired or creative or inventive.”

Much of the fun of these products comes from the combination of screens and physical play: building something then programming it via a device to do something. Koby thinks that the physical aspect is vital.

“We have hands!” she says. “We feel better making things than we do sitting behind desks. We have hands and a need to make things… Fundamentally, humans want to make. We feel productive when we’re making things. We’ve been building tools for centuries to fix things, to make things, to create new technologies. That act of making is fundamental.”