Sign-up to our mailing list

How we designed Fabulous Beasts

So, a few weeks ago, Fabulous Beasts completely changed.

Alongside creating its hardware, we’ve been developing the game itself, and for the longest time we’ve focused on a competitive one, in which two players face each other over the tower in a red-in-tooth-and-claw battle for supremacy with their beasts.

But we knew something was up with it. The game was fun, but also complicated and hard to explain. Getting it across to new players at busy public events was tricky, and we were about to take it to Spiel and then Indiecade. We needed to address some difficult questions, fast.

This is the story of how we designed Fabulous Beasts, and how we tore it all down and rebuilt it into something completely new. A bit like a Fabulous Beasts tower?

Meet George Buckenham. He’s Fabulous Beasts’ game designer and programmer, and a general indie game maker at large, as profiled on Rock Paper Shotgun. He’s made many games for events, like Punch the Custard and also Clandestine Candy, which was for Hide&Seek, Alex Fleetwood’s former studio. They got to know each other, and so later, when George heard that Alex was looking for a programmer for a new physical/digital game project, he jumped.

Fabulous Beasts’ core concept has always been a game that responds to the blocks in a tower, based on their order and whether the tower is standing or collapsed. But the theme has been less fixed. An early one was nature, of ecosystems and balance. George and Alex were interested in the idea of gods squabbling over a world, risking ecological collapse in the process, an idea that led towards a competitive game.

During this early period Fabulous Beasts was a product of REACT Hub’s Play Sandbox in Bristol. Play Sandbox is about designing with children, so we were showing the game to kids each month and getting their amazing feedback. Through them we learned how appealing the beasts were, and how making hybrids with the cross piece (take a look at Daily Fabulous Beast for examples) was super fun.

We also tried out some pretty ambitious ideas, such as simulating populations. George studied formulas that model relationships between predators and prey like foxes and rabbits, with the thought that they would play to the strengths of having a computer connected to the tower-building.

As George and Alex started refining the design, emphasising the fundamentals, things like population simulation started to disappear. They also wanted to follow the principle of subitising, which is the way people can immediately see how many objects there are in a group of five of below without counting. This was important because we wanted Fabulous Beasts to be visual, and for players to be able to quickly equate the relationships between animals in ecosystems by just looking: five eagles on seven toucans is fine, but six bears on two warthogs is bad.

The game kept evolving, and we showed it to lots of people. Their feedback was, well, very polite, and we found ourselves brushing off the more negative comments as less important. But then we took it to an event called Gamer Disco. There, people pretty much just wanted to play Nintendo, drink and dance, and they didn’t hold back. Someone asked, ‘Why is the game so complicated?’ and we didn’t have a good answer.

We realised the game didn’t quite fit with players’ expectations of a game based on building a tower. Since players didn’t have similar games to compare Fabulous Beasts to, we had help them understand what it’s about.

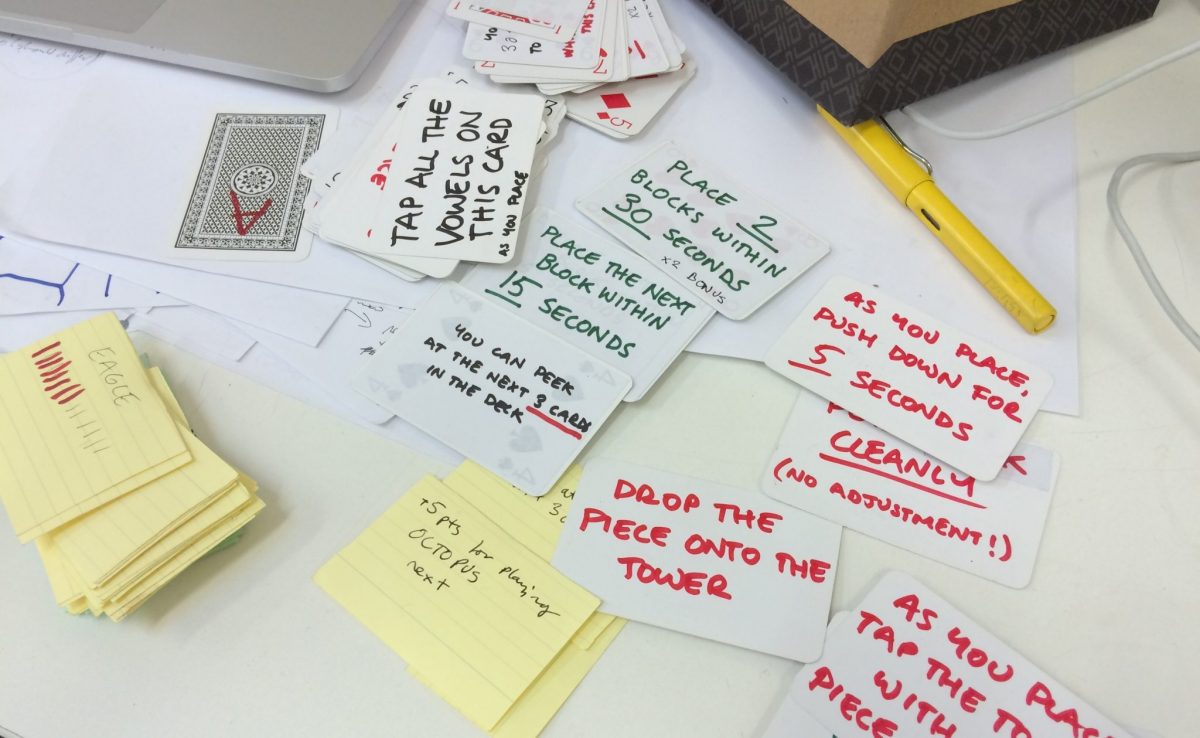

And so, with Essen approaching fast, we spent two weeks thinking up a new approach. We started seeing a cooperative game, and George and Alex drew up cards which gave instructions for placing beasts and awarded bonuses for completing challenges, such as placing large beasts on small ones.

It was okay, but it didn’t really fit with what we learned from the kids about how the beasts were the core appeal. Then, we came up with the idea of giving beasts individual scores. It gave them value, making you want to nurture them.

It also allowed building the tower to happen organically, rather than to a set of instructions. Constraints came as a natural result of previous decisions, and fun was a result of simply placing beasts. It worked brilliantly for kids and adults alike, giving different appeal to different people, whether they wanted to score big, see crazy hybrids or stack a great tower.

It also solved a tricky problem we’d previously faced in getting players to look at the screen or the tower at the right time. The focus was now, rightly, on the tower. We saw people suddenly starting to talk to each other, whether they were playing or watching. You don’t need knowledge of the game to have opinion about where a block should be placed, and people got opinionated quickly – even more so when they understood the scoring.

George started a new project in Unity, the game engine in which Fabulous Beasts runs, and built it over the month before Essen. We found players really liked it. The sense of relief in the studio was palpable – we’d been quietly uneasy with the game for a long time, and we’d finally made something that really worked. Here it is in action:

So it’s a story with a happy ending. But that competitive game hasn’t yet gone away yet. We like it too much. It needs some more love, but we’ve learned a lot from the past few months. We’ll keep working at it.

Thanks so much for reading. We’re taking Fabulous Beasts to Kickstarter on January 26. Come follow us by signing up!

And you can do a lot to help us, too. We don’t have vast budgets for advertising and marketing, so we’re super reliant on people like you helping to spread the word. If you have a couple of minutes, tell a friend who’d like Fabulous Beasts! And you can always contact us, on Twitter, Facebook or at hello@sensibleobject.com. We would love to hear from you.